Jesus therefore replied and said to them: Amen, amen, I say to you, the Son cannot do anything of himself, but only what he sees the Father doing. For whatever the Father does, the Son does likewise. For the Father loves the Son, and shows him everything that he does. [Jn. 5:19-20a]

753. Then when he says, For the Father loves the Son, he gives the reason for each, i.e., for the origin of the Son's power and for its greatness. This reason is the love of the Father, who loves the Son. Thus he says, For the Father loves the Son.

In order to understand how the Father's love for the Son is the reason for the origin or communication of the Son's power, we should point out that a thing is loved in two ways. For since the good alone is loveable, a good can be related to love in two ways: as the cause of love, or as caused by love. Now in us, the good causes love: for the cause of our loving something is its goodness, the goodness in it. Therefore, it is not good because we love it, but rather we love it because it is good. Accordingly, in us, love is caused by what is good. But it is different with God, because God's love itself is the cause of the goodness in the things that are loved. For it is because God loves us that we are good, since to love is nothing else than to will a good to someone. Thus, since God's will is the cause of things, for "whatever he willed he made" (Ps 113:3), it is clear that God's love is the cause of the goodness in things. Hence Denis says in The Divine Names (c. 4) that the divine love did not allow itself to be without issue. So, if we wish to consider the origin of the Son, let us see whether the love with which the Father loves the Son, is the principle of his origin, so that he proceeds from it.

In divine realities, love is taken in two ways: essentially, so far as the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit love; and notionally or personally, so far as the Holy Spirit proceeds as Love. But in neither of these ways of taking love can it be the principle of origin of the Son. For if it is taken essentially, it implies an act of the will; and if that were the sense in which it is the principle of origin of the Son, it would follow that the Father generated the Son, not by nature, but by will - and this is false. Again, love is not understood notionally, as pertaining to the Holy Spirit. For it would then follow that the Holy Spirit would be the principle of the Son - which is also false. Indeed, no heretic ever went so far as to say this. For although love, notionally taken, is the principle of all the gifts given to us by God, it is nevertheless not the principle of the Son; rather it proceeds from the Father and the Son.

Consequently, we must say that this explanation is not taken from love as from a principle (ex principio), but as from a sign (ex signo). For since likeness is a cause of love (for every animal loves its like), wherever a perfect likeness of God is found, there also is found a perfect love of God. But the perfect likeness of the Father is in the Son, as is said: "He is the image of the invisible God" (1:15); and "He is the brightness of the Father's glory, and the image of his substance" (Heb 1:3). Therefore, the Son is loved perfectly by the Father, and because the Father perfectly loves the Son, this is a sign that the Father has shown him everything and has communicated to him his very own [the Father's] power and nature. And it is of this love that we read above (3:5): "The Father loves the Son, and has put everything into his hands"; and, "This is my beloved Son" (Mt 3:17).

Of special interest is the third paragraph in which Aquinas speaks of love in divine realities. Aquinas completely rules out the possibility that love is the origin of the Son's procession from the Father. If the principle of the Son's origin is the love of God taken essentially (i.e. the love of God as God in the unity of His being), this implies a decision of God's will and thus the creation of the Son, i.e. Arianism. If the principle of the Son's origin is the love of God taken personally (i.e. as the Holy Spirit proceeds as Love), it would follow that the Son proceeds from the Holy Spirit. Aquinas knows of no heretic so foolish as to hold this!

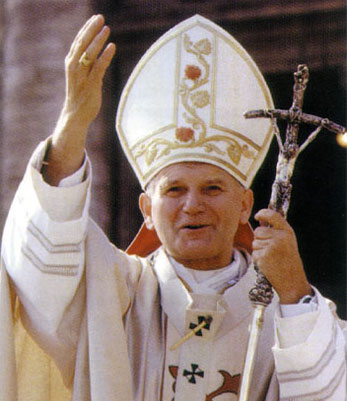

Of special interest is the third paragraph in which Aquinas speaks of love in divine realities. Aquinas completely rules out the possibility that love is the origin of the Son's procession from the Father. If the principle of the Son's origin is the love of God taken essentially (i.e. the love of God as God in the unity of His being), this implies a decision of God's will and thus the creation of the Son, i.e. Arianism. If the principle of the Son's origin is the love of God taken personally (i.e. as the Holy Spirit proceeds as Love), it would follow that the Son proceeds from the Holy Spirit. Aquinas knows of no heretic so foolish as to hold this!Contrast this with John Paul II's teaching in his theology of the body, where the origin of the Son is said to be rooted in the Father's "gift of self" (read: act of love). Apparently this is why many Thomists are unimpressed (to say the least) with John Paul's work, while many disciples of John Paul are more than ready to abandon the Universal Doctor of the Church. Interesting indeed; I intend to follow up on this and see what more I can learn. [UPDATE: I should add of course that I suspect that Dr. Waldstein thinks the two positions reconcilable. I still hope to hear from him how this is so.]

5 comments:

I don't think that you need to read "gift of self" as "act of love," at least if by 'act' you mean an 'act of the will.' The Father's gift of self is more radical, and, if you will forgive the term, existential. For the Father /is/ His gift of self: the Father is entirely poured out into the Son, and the Son entirely poured back into the Father, not as acts of the will so much as that is what they are. Thus I don't think that John Paul's idea (nor the ideas of Von Balthasar) need to be interpreted as a sort of Arianism. John Paul is certainly working with a different theory of 'act' than Thomas, and he is working out of a more 'phenomenological' and existential framework than Thomas too (although Thomas certainly has good phenomenological rigor too!)

That's how I have always interpreted John Paul. It is certainly an interesting dichotomy between the two, to say the least, and much work needs to be done on this issue. God bless,

Mark

Of course, it is an "act of love" if you understand 'act' in a broader sense that just 'act of will.' For God /is/ Love, of course, and so all that He does could be called an 'act of love;' Thomas too indicates this total gift of self in the final paragraph that you quote, only he calls it "communication." For John Paul II, this communication, the very begetting of the Son by the Father, is a gift of self, an outpouring of His very existence, which is itself His self.

Why can't the Father will the Son so long as He wills Him eternally? We know that the Son proceeds forth from the Father eternally, so wouldn't it be the case that the Father wills this? I don't see the connection between God willing the Son and creating Him. Could you please elaborate?

WOC, thanks for your comments, that sounds plausible.

Boniface,

I'm afraid I can't elaborate. This was the thumbnail sketch given to us in class this morning, and I haven't yet managed to sit down and talk about it at more length with Dr. Walstein.

Ah, the old bait and switch!

Post a Comment